When Liz Lange walks you through Grey Gardens — the East Hampton home made famous by the 1975 documentary that showcased its eccentric inhabitants living in transcendent squalor — you will notice that very little is gray.

Since Ms. Lange bought and renovated the place, bulbous turquoise chandeliers dangle from the ceiling, blue leopard wallpaper lines the entryway, and painted wicker chairs and gold flamingos abound.

There are still gardens aplenty. A walled garden flush with dahlias and digitalis is on one side of the house, with a topiary garden on the other. There is also a discreet plot, etched with an elegy to a loved one of the home’s famous former residents, Big Edie and Little Edie (both Bouvier Beales): “Spot Beale. A nobler gentleman never lived. Beloved by all who knew him. Died May 29, 1942.”

Here, Ms. Lange, 55, walking barefoot and wearing a paisley caftan, broke pace to reflect. “The WASPs really know how to bury their dogs,” she said.

The Beales were Catholic, not Protestant, but Ms. Lange was using the acronym as a catchall for an erstwhile white, Christian, wealthy class of power brokers and tastemakers. That upper crust loomed large in the minds of some 20th-century immigrant families whose American dreams involved bulldozing past the stuffy guardians of the financial, educational and cultural institutions that conferred status.

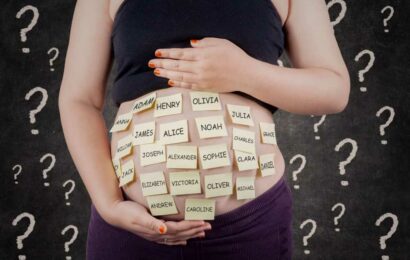

Ms. Lange made her name as a maternity wear designer. More than a fashion line, the Liz Lange brand reshaped the way many women thought about dressing while pregnant, eschewing Peter Pan-collared muumuus in favor of fitted, sophisticated styles in stretchy materials that followed contemporary women’s wear trends. She started the company in 1997 and sold it to a private equity firm a decade later for tens of millions of dollars.

Lesser known is that before she was Liz Lange, she was Liz Steinberg, a scion of the corporate-raider family led by Ms. Lange’s uncle Saul Steinberg, the chairman and chief executive officer of Reliance Group Holdings, and her father, Bob Steinberg, his deputy.

The excesses of 1980s new-moneyed New York City were embodied by the Steinbergs, especially Ms. Lange’s publicity-loving Uncle Saul (who died in 2012 at 73) and his third wife, Gayfryd.

Saul and Bob, the Brooklyn-born grandchildren of Russian and Polish Jewish immigrants, elbowed their way to vast wealth, instilling in their family a sense of mission to use brains and bank accounts to push past old-money gatekeepers. When Ms. Lange was growing up, she heard her relatives banter about the diminishing power of that ruling class. “Lots of lineage, no dough” was a common family refrain, she said.

What Ms. Lange didn’t see coming is that before long, “no dough” applied to the Steinbergs too.

Family Business

Ms. Lange had always toyed with the idea of sharing her family story. If the world fell in love with “The Sopranos,” she reasoned, why not the Steinbergs?

“‘Mobsters: They’re Just Like Us,’” she said, describing the appeal of the HBO series about New Jersey mafiosos as she sipped cranberry and club soda from a settee on her front porch.

“He’s got trouble with his kids, he’s got tsuris with his wife,” she went on, using the Yiddish word for “trouble,” “his mother’s a pain, we all could relate.”

Stuck at home during the pandemic, she agreed to record a podcast episode about her life with her close friend, the journalist Ariel Levy. But there was so much material, Ms. Levy decided to make an entire series. The result is “The Just Enough Family,” which draws on Ms. Levy’s interviews with Ms. Lange; her sister, Jane Wagman; her mother, the realtor Kathryn Steinberg; her father, Bob; and her aunt Gayfryd.

It’s the story of how a middle-class Jewish family from Brooklyn transformed a rubber business into a financial conglomerate that paid massive dividends to Saul, Bob, their two sisters and their mother — who eventually sued her sons when the opulent lifestyle of birthday parties at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and private travel on 727s met its inevitable end.

In 1995, Saul suffered a debilitating stroke which left Bob mostly in charge. But in 1999, Reliance’s performance tanked, with losses of more than $300 million, and Saul fired Bob. By 2001, the company was bankrupt.

The podcast centers on Ms. Lange’s memories of her own experiences, which include surviving cervical cancer, her first husband’s struggle with mental illness, and the discovery that Bob, whom Ms. Lange revered, had a secret life. The first two of eight episodes drop next week.

Her self-reflection took root early in the pandemic, as she poured herself into her Instagram feed, sharing photographs from the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, with nostalgic captions about her youthful yearnings to effect Christie Brinkley’s hair (“I used to take my hair diffuser, fill my hair with mousse, turn my head upside down”) and onscreen obsessions, like Tatum O’Neal, Kristy McNichol and Matt Dillon.

Chatting online with her followers reminded her of her early days at Liz Lange, when she talked directly with customers about how clothes influenced their confidence in the workplace.

This stoked her own professional confidence, and late last year, Ms. Lange purchased Figue, a line of caftans and flowy dresses sold at Neiman Marcus and Shopbop. (Items range in price from $295 to $1,500.)

“Before the pandemic, I spent a lot of time teetering around in high heels and tiny dresses and it wasn’t terribly comfortable,” she said.

“Liz was seeing everyone dressed in sweats and athleisure and with Figue, she is saying, ‘That’s great but can we add a little glamour and hedonism?’” said her friend Simon Doonan, the author and former creative ambassador of Barneys New York. (He is also the husband of Ms. Lange’s best friend since college, Jonathan Adler.)

“I’ve gone hiking with Liz, and she wears a caftan,” Mr. Doonan said. “She knows that we would have never seen Marisa Berenson and Bianca Jagger in yoga pants.”

Ms. Lange’s first designs for Figue will be released in October. “I finally fully feel like myself again professionally,” she said.

An ‘Identity Crisis’

When Ms. Lange came up with her novel approach to maternity wear in the mid-1990s, she was a college graduate working as a fit model and a fabric buyer for an upstart fashion designer. She had recently married Jeff Lange, a hedge fund executive, and as many of her friends began to get pregnant, she noticed that they either stuffed themselves into clothes that didn’t fit or wore ugly tentlike dresses.

Taking a $25,000 loan from her father, she made samples of maternity designs in stretchy, form-fitting fabrics and reached out to friends and celebrity publicists to offer made-to-order services. Word spread, and soon she had a crush of business.

Pregnant actresses and models were shown in magazines like People wearing her pieces. Nike asked her to help develop a maternity line with the brand and she entered a partnership with Target.

Her first show at New York Fashion Week — the first maternity show ever held there — was on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001. As her models walked the runway, Ms. Lange noticed videographers from CNN and “Good Morning America” racing from the venue’s tent.

By October, Reliance was bankrupt and ordered to liquidate. That same month, Ms. Lange was diagnosed with cervical cancer.

Shaken by the tumult and urged by her first husband to cash out, she sold Liz Lange in 2007. Ms. Lange said the price was in the range of $20 million to $60 million.

After the sale, though, she realized that she had walked away from more than a job. “I felt a true sense of loss,” Ms. Lange said. “It was almost like an identity crisis.”

She had more time to spend with her children, Alice, now 20, and Gus, now 22, but the fissures in her marriage became more evident too. She and Mr. Lange separated in 2009 and finalized their divorce in 2014. (Mr. Lange died in 2018.)

Renovation and Rejuvenation

Ms. Lange had continued to work with Target as the face of the brand she no longer owned and spent a few days a month selling an affordable line on the Home Shopping Network. It was a lucrative gig, but by 2018 she was bored and quit.

At that point, she was with her current husband (a corporate attorney who asked not to be named in this article because the media mishegas is not his thing). They married in 2015 at Grey Gardens, which they had rented.

In 2017, they bought the house for $15 million from Sally Quinn, by then the widow of Ben Bradlee. Though the house had been refurbished after its days of Big and Little Edie, Ms. Lange had something more extensive in mind. She oversaw a renovation that included the house being lifted to accommodate the addition of a 4,000-square-foot basement.

She brought in Mr. Adler to help her with the interiors. “A good interior designer should be a like a slimming mirror for your client,” he said, “reflecting her at her best.” The result is a colorful smorgasbord of what Mr. Adler calls “eccentric American glamour” with undeniable overtones of WASP style (think shabby chic — minus the shabby, plus a little L.S.D. and a lot of money).

Last summer, in the sunroom that looks out onto the walled garden, Ms. Levy conducted podcast interviews with some members of the Steinberg family. The project offered an opportunity for them to connect during the pandemic, said Mr. Steinberg, 78, in an interview. “I’m a private person,” he said, noting he had, in his professional heyday, avoided press. But his daughter’s friendship with Ms. Levy assuaged him. (Reminded that it was in part his brother’s courting of attention that led to the family’s tabloid status as a cautionary tale, Mr. Steinberg replied, “I’m well aware.”)

Ms. Lange is curious, and a little nervous, to witness the response to her family saga, rife as it is with money and privilege. “I don’t think my family story is more important or even as important as many of the other stories being told today,” she said. “But I do think it’s a pretty crazy story, and who doesn’t love a crazy story?”

Source: Read Full Article