By Richard Flanagan

MemorialCredit:Julian Kingma

I rang Brian, my oldest and one of my dearest friends, and asked if he’d like to watch Nitram with me. On the fatal Sunday afternoon of April 28, 1996, Brian, then a police constable, was choppered along with another constable to the Port Arthur historic site, the first police there and, until armed reinforcements arrived two hours later, the only police.

As the chopper landed, he was shocked to see scores of people emerging out of hiding places under buildings and in trees and running towards them, believing he would protect them should the gunman, who had only left a short time before, return.

Nothing could have prepared Brian for what he now discovered: the dead everywhere, the dying, the many wounded. Brian quickly gathered that the gunman had a high-powered semi-automatic hunting rifle, murderous at a great distance. Tasmanian police at the time were armed with a small revolver, the Smith & Wesson .38.

In Tasmania, everyone has a story from that time – their own or that of a friend, a relative, a workmate.Credit:Anthony Johnson/Fairfax

I remember Brian pointing to our kitchen door.

“I am a fair shot,” he explained. “And with a Smith & Wesson, I could hit a target in that doorway. But beyond that? Probably not.”

If the gunman returned Brian knew he would not be able to protect those who now trusted him to keep them safe. And that knowledge tormented him terribly: what he would have done, what he could have done, and could not have done, what might have unfolded on his watch.

When there were reports of gunfire at the nearby Fox & Hounds Inn, Brian, with only his revolver, went to investigate. I still get upset thinking of his courage in doing that, not knowing what fate awaited him.

Art must say the unsayable: Tasmanian artist Rodney Pople’s painting, Port Arthur, won the Glover Prize for landscape in 2012.Credit:Courtesy of Rodney Pople

In Tasmania, everyone has a story from that time – their own or that of a friend, a relative, a workmate. The close intertwining of society here meant no one was unaffected. And in that way of connection, I became a friend of Justin Kurzel when he married another friend, the actor Essie Davis, whom I knew through her brothers who were good friends of both mine and Brian’s. My mother taught Essie’s father, George, a celebrated painter. My sister taught Martin Bryant, the Port Arthur mass murderer. Everyone has a story, and in Tasmania every story connects.

In Tasmania, everyone has a story from that time… The close intertwining of society here meant no one was unaffected.

Kurzel became a director. With the screenwriter Shaun Grant, he made Snowtown and now Nitram. They are working on a television adaptation of my novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North. There is a line in that novel: Man survives by his ability to forget but freedom exists in the space of memory.

It’s about a character in the book. It’s also about Tasmania.

Grant had told me how he had been sickened by the gun culture in Los Angeles where he had moved to work as a screenwriter. One day, he saw a television news report on children being trained at a local school to survive a massacre. Horrified, he wrote the screenplay of Nitram in a frenzied eight weeks, fashioning out of the Australian story of the Port Arthur massacre an argument, an answer to the madness that consumes American society. It was his attempt to stop things like Port Arthur recurring.

When controversy engulfed the making of Nitram last year – fundamentally misrepresenting the purpose and focus of a film no one had seen and, in the way of social media, exaggerating and amplifying that misrepresentation – I understood why some survivors would have no desire to see the film.

But I did not agree with those, no matter their experience, who said this film should not be made, or, once it was made, say that it should not be shown.

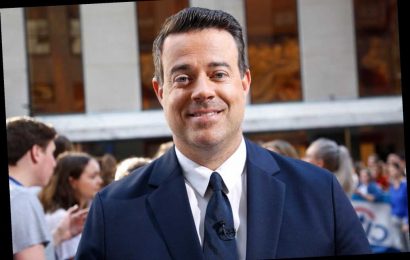

Sickened by American gun culture, writer Shaun Grant wrote Nitram in eight frenzied weeks.Credit:AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda

Nor did I agree with those arts bodies which abandoned the project despite the reputation of the filmmakers and their intent, almost ensuring it was never made. Film Victoria’s board declined to fund it because of the subject matter. Screen Australia’s board declined to fund it because of the subject matter. To make the film, its makers and actors had to help finance it out of their own pockets.

Worse, the Tasmanian Premier Peter Gutwein didn’t reply to offers of a meeting with Kurzel so that he might explain his intentions and address fears about the film. Tasmanian Attorney-General, Elise Archer, declined meeting with Kurzel and producer Nick Batzias denying them the ability to access the Victims of Crime Service to allay Port Arthur victims’ concerns that the film was in any way insensitive or exploitative. Archer, who is also the Arts Minister, wrote to Batzias, “I do not believe it is appropriate for the Tasmanian government to lend support or enter into discussion regarding this project.”

And what is this Tasmanian Liberal government that refused to support an anti-gun film made by Tasmania’s most eminent director?

Well, it is the same Liberal government that days before the 2018 Tasmanian election was revealed to have made a secret deal with a firearms consultation group to soften gun laws. The then police minister and former Liberal state leader, Rene Hidding – presently facing child sexual interference allegations in the civil court, allegations he ‘vehemently denies’ – promised shooters the Tasmanian Liberal government planned to soften the state’s gun laws, extending gun licences from five to 10 years, abolishing mandatory weapon removal for minor breaches of firearm storage laws, allowing “certain specialists” to use presently banned guns, and pushing nationally to allow “a greater range of sporting shooters to use pump-action and rapid-fire shotguns”.

Essie Davis as Helen in Nitram.

These promises, which did not become public until the eve of the election, would have breached the national firearms agreement and were not supported by the Federal Coalition government of the day. It was one more chapter in the long and strangely entwined history of the Tasmanian Liberal Party and the gun lobby which in the past, according to Roland Browne, vice-chairman of Gun Control Australia, “wrote the state’s gun laws.” In 1985 the then Robin Gray-led Liberal government subsidised a Hobart factory to manufacture semi-automatic military rifles, one of which, after the Port Arthur massacre, was found in Martin Bryant’s home. In the wake of two Melbourne mass shootings in 1987 the same Tasmanian Liberal government succeeded in frustrating national gun controls being introduced, leading the then premier of NSW, Barrie Unsworth, to declare, “It will take a massacre in Tasmania before we get gun reform in Australia.”

I come from a society of silence and silencing. Martin Bryant understood something of this.

I come from a society of silence and silencing. Martin Bryant understood something of this. “A lot of violence has happened there,” he reportedly later said of Port Arthur. “It must be the most violent place in Australia. It seemed the right place.”

The penitentiary building: “It must be the most violent place in Australia. It seemed the right place,” Martin Bryant reportedly said.Credit:iStock

Since the time Port Arthur was a terrifying prison where convicts were subjected to what was a revolutionary program of silence and surveillance underpinned by violence, fear has been used in Tasmania to stop people living in freedom and speaking their truth.

Silence, above all, enables the abuses of power and privilege that have continued to this day on my island.

And what we may think of as an historical anachronism unique only to Tasmania we now see renascent in the Morrison government’s conspiratorial secrecy, evasions, and contempt for a civil society’s freedom to express itself. It is perhaps no surprise that when that defiant Tasmanian, Grace Tame, said “Hear me now” on winning Australian of Year her words had such profound national resonance, and not only for women.

For we discover – to our surprise that really should be no surprise at all – that we no longer function as a nation, but as sad, isolated states squabbling over vaccines, definitions, the speed or slowness of public health responses to our greatest crisis since World War II.

But we shouldn’t be shocked. Because we have been drifting this way for a very long time. The slow corrosion of our national institutions and our national polity now manifest as a failing central state begins not in politics but in the abandonment of any collective dreaming of who we are and what we might yet be.

Judy Davis plays Mum in Nitram.

We see it in the contempt shared by both Liberal and Labor for the role of art to have any place in who and what we are as a nation. I visited our national art gallery in Canberra in June to discover that this great institution at our centre – born of a bi-partisan vision of Australia not as a federated set of colonies but as a true outward-looking nation open to many voices, established under Harold Holt, begun under Gough Whitlam and completed under Malcolm Fraser – now so reduced that buckets were scattered throughout to catch the dripping water from a leaking roof as if it were one of those sad dilapidated cultural institutions you might find in a collapsed state. The gallery’s passionate director, Nick Mitzevich, told me last week that money has finally been found for the long-standing problem of the leaks, but that realising the immense potential of the national collections remains a struggle.

We see it in the way the Australia Council is scarcely even a soup kitchen for Australian writers who, in total, receive less than $2.4 million in annual direct grants. We see the silencing most perfectly exemplified in the crisis besetting the National Archives which, similarly starved of funding despite a recent emergency top-up, now risks the loss of everything from recordings of the wartime speeches of John Curtin to the diaries of the suffragette leaders to records of the Bounty mutineers. The crisis is so extreme the Archives’ departing director, David Fricker, admitted that the institution’s inability to maintain all its records puts it at danger of breaching its own Act, while constitutional law expert Anne Twomey described “the memory of the nation,” as being at risk.

At the same time, there is no end to the countless millions wasted on futile wars, endless Anzacery, and military museums, a sickly miasma out of which arises one of Australia’s principal foreign policy achievements of recent years: a global reputation for war crimes.

Caleb Landry Jones in the title role of Nitram.

And so to witness a film, conceived in rage against American gun culture as an anti-gun film, be pilloried and attacked all over social media and in mainstream media was deeply troubling. Worse, to know those charged with helping voices be heard were intent on smothering them at birth. And yet who was working to distress the survivors? The filmmakers, who from the beginning attempted to reach out to survivors to explain that the film was about the causes of violence, not the massacre itself, or the trolls on both Twitter and in opinion pages, saying this film’s aim was one of exploitation and sensationalism?

Aware of the controversy that had already beset Nitram, Brian and I watched the film. And at its end, Brian turned to me.

“Well,” Brian said, “there’s nothing offensive in that.”

And there isn’t. The massacre is never shown. Caleb Landry Jones’ portrait of a murderer, which won him the best actor award at Cannes, while insightful and revealing, cannot be confused with sympathy or empathy. Whatever the film is, it is not exploitative or sensational. The most disturbing scene is when the gun shop happily sells high-powered guns to a clearly disturbed young man.

Director Justin Kurzel, left, and Caleb Landry Jones at Cannes.Credit:Vianney Le Caer/Invision/AP)

As a friend of the director, I won’t offer any public judgment of the merits or otherwise of Nitram as a film. But I will venture an observation. It’s a COVID film, about people who are unable to communicate, lost in bubbles, trapped, and the tragic consequences that ensue. In that sense, it is the perfect allegory for Morrison’s locked down Australia in 2021. There has been too much silence, too many taboos about what we can and cannot talk about, and worse, who is allowed to speak.

Fear and silence go hand in hand, and misinformation and untruth are the energy that propels them forward. Art, when it does its job properly, is a necessary form of truth. It is the role of art to make us look at what we don’t wish to see, to say the unsayable, to rub against the grain.

Some years after the massacre I met a very brave woman who had worked at the Port Arthur site. When Bryant came out of the Broad Arrow Café after his killing spree there he fixed his rifle sight on Brigid Cook, who was helping others escape. She didn’t turn and flee. She didn’t flinch or bow her head. Instead, she looked directly at him, staring him down. He lowered his rifle and shot her in the leg.

A quarter of a century has elapsed since Port Arthur. It’s time we stopped running and started following that brave woman’s lead, staring the gunmen and their evil down.

Everyone has a story and every story connects, and every story needs to be heard. Don’t fear Nitram. Watch it.

Nitram is releasing nationally on Thursday where cinemas are open and will roll out in other states as they come out of lockdown. It will debut on Stan (owned by Nine, publisher of this masthead) later this year. Tasmanian author Richard Flanagan won the Booker Prize in 2014 for The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

How have we come to this?

An extract from an article written for The Age by Richard Flanagan on the evening of the massacre in 1996.

As I am writing this, the siege of the gunman continues. Details are few and unreliable, except for the body count, which continues to rise. As of yet, so little is known and yet some things seem clear. We must have strong laws that forbid the ownership of semi-automatic and automatic weapons, and which make the licensing of shooters as stringent as possible, and these laws must be enacted as a matter of the utmost priority.

It is wrong to blame what happened on movies or other forms of popular culture. But it is right to ask for a culture that stops being so obsessed with the moment of violence, and instead starts to examine the consequences of violence, and then not simply in terms of physical injury and mutilation, but in the decades and often generations of suffering that ensue. There does seem about the whole horrific affair a dreadful cinematic gloss, from the wisecrack at the door of the restaurant about there being more WASPs than Japs, through to the opening killings in that most pulp fictional of settings, the restaurant itself.

It is perhaps not possible to write anything of sense of such a senseless event, a passage of horror that can perhaps never be explained. And yet, some sense has to be made of it, or we cannot begin to try and stop such a thing ever happening again. The massacre is only meaningless if we capitulate to its madness as inevitable, as part of the human condition that we must now tolerate.

Some sense has to be made of it, or we cannot begin to try and stop such a thing ever happening again.

We need to rediscover that as people we need others not to kill, but to love. And for that, we need to rediscover that we are communities. It is possibly a sign of the times that I feel foolish writing such a thing, but it is all I have to offer against what has taken place. My children sleep well, but now I wonder for how long. There are no more once upon times, only nows, and I will have to explain something of this to them. But though I have tried, I cannot answer the insistent question that haunts me and everyone else I know this night as searchers discover yet more and more bodies: How have we come to this?

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article