TANYA GOLD: Wild camping touched my soul… but I’ll NEVER go again!

- Tanya Gold braved the wilderness with her husband, son and terrier, Virgil Dog

- READ MORE: Rules explained on where you can pitch a tent in the wilderness

Wild camping is all the rage now. Europe is burning and prices are rising, so why not turn off the M5 and treat the Dartmoor National Park as your personal hotel?

Dartmoor is the only place in England where you can ‘wild camp’ without landowner permission.

Wild camping has only one principle: no facilities except those nature gives you. Your running water is a stream, your toilet is a hole in the ground (which you must dig), your shower block is a waterfall . . . or nothing.

You must carry everything you need in your rucksack, stay only a night or two in one place and, above all, leave no trace: no large groups or large tents, and take your rubbish with you.

Local landowners, a hedge fund manager and his wife who own a 4,000-acre estate, recently tried to have wild camping on Dartmoor banned, arguing it could not be considered ‘open-air recreation’ — which is allowed in the national park —and wanting to revoke permission to their land for camping.

Tanya Gold went wild camping for two nights with her husband, Andrew, their son, who is ten, and the terrier, Virgil Dog

A High Court ruling went in their favour but they were thwarted on appeal, so it is an especially precious right — and campaigners are hatching plans for legislation to widen the right to wild camp across the land.

My interest is piqued, and I decide to wild camp for two nights with my husband, Andrew, our son, who is ten, and my terrier, Virgil Dog.

I am not a natural camper. I camped at Glastonbury 15 years ago where I awoke to find someone weeing on my tent (I watched his silhouette from my sleeping bag) and in the Isles of Scilly two years ago where I woke up with a mouth filled with sand, crying: the perils of a beachside campsite.

I have also stayed in a campervan at a Caravan Club site, which was like a village after a tornado — it was as organised as a village — except everyone was in a good mood.

Andrew, however, is a fine camper. He says camping is about the prep. The balance between what you need and what you can actually bear as a load is the essential thing.

Whistling, he assembles the gear and packs loads of (expensive) specialist camping food that comes in pouches: the kind of thing that survivalists stockpile, so they can eat through a nuclear winter. He says I cannot bring a duck-down pillow.

Our first stop is the visitor centre in Princetown, which is gloomily dominated by Dartmoor prison. The woman behind the counter smiles. I want to camp near the famous Wistman’s Wood, I tell her: I have always wanted to see it.

She wears a face of sceptical kindness. ‘How heavy are your packs?’ she asks. Heavy, I say (I brought the big saucepan). Hmm, she says, and leads me to a vast map on the wall. Rather alarmingly, it says ‘danger area’: the Army has a firing range here.

You cannot just camp anywhere on Dartmoor: there are vast designated areas. She points out two suitable spots: one at the base of a granite- capped hill (called a tor) beyond a wood, another at the top of a valley.

I should try these, she says. The walk from Wistman’s Wood to a permitted area will challenge me. (I think the unspoken part is — we don’t want to call out search and rescue because you fell over). Best to be near the car park, she says, until I get ‘good at it’.

When I am good at it, she adds, I will purify water from streams. We have four litres in bottles, and a nine-litre see-through plastic thing you wear as if you are a camel, which I end up not using because it’s stupid — and I need to travel light.

Backpack camping — she tells me not to call it ‘wild camping’, presumably because the word ‘wild’ encourages people to leave their ‘droppings’ on the ground, and not bury them — is a skill to be mastered.

We drive to Wistman’s Wood across fabulous landscape. Dartmoor is eerie, the setting for The Hound Of The Baskervilles, which I have brought along to read.

We see sheep, cows and tiny ponies: they stand in the road. This is their time. It’s always their time here: Virgil Dog must stay on a lead. We park and walk towards the wood.

Wild camping has only one principle: no facilities except those nature gives you. Your running water is a stream, your toilet is a hole in the ground (which you must dig), your shower block is a waterfall . . . or nothing

Half an hour later we stand at the threshold of Wistman’s Wood. We cannot go in: the ecosystem is too fragile, and someone apparently stole moss from the trees for their hanging baskets during lockdown.

But it doesn’t matter. I can see oaks sprouting from granite boulders, moss covering each bough. It is a tiny surviving part of England’s ancient forest, and it is everything I thought it would be. I stare at it for a long time, and I’m so glad I came.

We drive south-east to Burrator Reservoir. Andrew makes me navigate to our spot from the Ordnance Survey map: he has banned mobile phones for the weekend.

I find the map very absorbing, though confusing: everything that can be put on there — church, post box, farm — is marked. I get us to the car park without using Google Maps.

We load our packs. Tents and water bottles and sleeping bags and pans hang off me. I feel like a donkey.

My husband copes better but he is from a Scouting family; his mother represented the Girl Guides at the national jamboree.

We walk slowly — we have no choice — through glorious woods. Someone, Scouts probably, have built a series of shelters with boughs, sticks and moss. Our ten-year-old plays in them, enchanted.

We reach a wall and a stile and we are under a tor. It is amazingly beautiful: I just wish there was somewhere to sit down. The ground is surprisingly soft. It’s a good place to camp.

The boys throw up the tents without fuss while I set up the gas camping stove. I put it on a lump of rock for our dinner-from-a-pouch. Do not start fires is probably the first rule of backpack camping.

I empty what is apparently chicken tikka into the pan. Soon, it is hot. I spoon it into lightweight plastic bowls, and we eat it with plastic cutlery that has a fork on one end and a spoon on the other. Nifty.

The food is hot, as I said. It is also unbelievably gross, and I cannot eat it, though the boys are fine.

I miss supper that night: I subsist on an emergency Toblerone. I did a survivalist course once where we were taught (theoretically) to shoot deer with bows and arrows and dig pits with sharp stakes at the bottom to kill passing pigs.

The instructor suggested that if I find myself living in a wilderness, I should eat invertebrates, such as insects and worms, which I think means that I failed the course.

Because I cannot eat pouch food, the sheep begin to look pretty tasty. I don’t know how experts stop themselves. (Amazingly, eating the sheep is banned. Perhaps that is another reason we have to call it ‘backpack’ camping).

After supper, there is nothing to do except read The Hound Of The Baskervilles, so we go to bed. I brought pyjamas for my son (they instantly get wet when he sits on the ground) but we sleep in our clothes.

My son wakes up at midnight, whimpering: he secretly read the back of The Hound Of The Baskervilles, he admits, and is frightened. He wants to sleep in our tent. He gets in. My husband moves to the boy’s tent, which is the size of a coffin.

I fall asleep quickly but wake at 2am for the dreaded and inevitable camping ritual: the dead-of-night wee. I stumble out of the tent miserably . . . and then I see the stars.

I have never seen so many, and the more I look the more I see. I am mesmerised. It is like touching God, and Man both: all humans who have ever lived have lived under them.

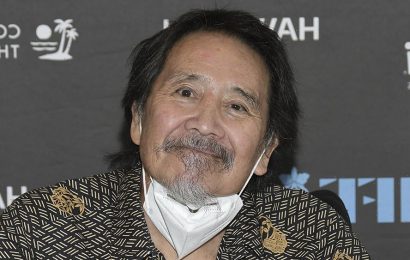

Tanya and her husband Andrew with Virgil Dog during their wild camping expedition in Dartmoor

I wake at dawn, open the tent and see mist. I eat a cold croissant, lying down, without butter or jam. My son and I make coffee (I cannot live without coffee, I brought my Italian coffee maker) while Andrew sleeps; he can sleep through anything.

When a cloud of midges invades the tent, I realise we may have camped in a bog in error. These are my first insect bites. There will be many more.

We pack up and walk in the woods. I feel happy and peaceful — I liked the stars — but I am also beginning to feel dirty. I do not like feeling dirty.

We see a small waterfall. I take off my pack and wash my face in the clear spring water. It is the face wash of my life; it is glorious. My husband tells me to drink some.

I don’t want to, I say. There might be sheep poo in it. There are no sheep, he says, I can’t see any sheep here.

I can’t see any Russians, I reply, it doesn’t mean they don’t exist. He looks at me as if I am mad. I drink the water. It is delicious. I wish I had brought a towel, and a swimming costume, or just a towel so I could swim nude.

Along with eating sheep, I’m not sure if this is allowed. In the Dartmoor wild swimming guide, everyone is wearing swimming costumes while jumping gleefully off rocks. I have yet to see someone nude.

Andrew, who, I now realise, loves wild camping because he hates people, and there aren’t any here, is obsessed with the map. He stares at it and strides quickly into the wilderness, following its paths. When I think he is marching us in circles I check Google Maps and I am right: he is marching us in circles.

I tell him — from Google Maps — the real quickest way to the car park, after which he sulks. (‘I wasn’t lost,’ he says now. He makes me type it out on to this page). I sulk back.

Tonight it’s pouch night again — chilli con carne (or, rather, a grim impersonation of it) and I will not have it. I am a food critic, among other things, and I will not eat apocalypse food.

I’d rather eat a sheep and that is not an option. He must drive me to the M&S at the Exeter services, or I am out of here.

At the M&S I buy Greek salad and tabouleh and yogurt and more croissants and Toblerone. I also have a cheeky full English breakfast. I wash up the chicken tikka pan in the loos.

We drive back to Dartmoor and into the hills: we park and walk to find a campsite. We meander along the road and Andrew points to a field of bracken: that way, he says. My insect bites are stinging, and I refuse to go into the bracken, which is a city of insects.

I whimper. My son whimpers. Andrew harrumphs and leads us back to the car park, and we look for a camp as close to it as we are allowed.

Anything that is not bracken is cow path. I can hear them but I cannot see them. I secretly Google ‘trampled by cows + Dartmoor’ but there is nothing. We find a spot. There is a lot of dryish cow dung. But no bracken.

Backpack camping is made of such trade-offs. You want a goose-down pillow? Carry it on your head. You want hot and filling food? It will taste gross. You want to be close to God? Eat mud.

Speaking of dung: hello, wild camping poo. You dig a hole. But not with a spade. Who brings a spade? You attack a circle of earth with a small shovel. Then you peel off the top layer of turf and dig further, to a depth of 15cm.

Then you replace the turf, and place two crossed sticks on it as a warning to other campers: a personalised skull and crossbones. I can write no more on it. This night is the worst. They cook the pouch food: even Virgil Dog will not eat it, though Andrew does, and I give my son emergency croissants. Then bed.

My son cries in his sleep and I tell him to come into our tent. I see the stars, brighter than ever before, and I go into the boy’s tent. I use the torch to open it. Insects flock to me: it’s like the scene in Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom. I scream, rise and almost pull both tents down.

The next morning, I have 58 inflamed insect bites. They swell and sing to me. The morning croissant (no butter or jam) is ashes in my mouth. I want my bed, I want my bath, and Virgil Dog is no better. He is not used to giving way to sheep or being on the lead outdoors. He stares beseechingly at me. His eyes say: is this for ever? Where is the sofa that I loved?

We pack up and leave to find a shop that sells antihistamines for the bites. My socks are wet. When I take them off in the car my husband howls and opens the window. I leave Dartmoor thinking backpack camping should be available to everyone and facilitated across the country. If well organised, it could transform our wellbeing, particularly our children’s.

Instead of the screen, the sky, and instead of the Tarmac, the wood and the water. I do not know when it became so British to be fat and immobile, and not to know this.

My husband adores it and is already planning a return. He is drooling over minute stove systems and frying pans with detachable handles and medium-priced ponchos.

But it’s not for me: I wish it were. I can see its possibilities. I see myself with a block of fine cheese in one pocket and salami in the other — and maybe French sticks crossed like swords in the backpack — walking the trails, splashing in the rivers, knowing the earth and loving the stars. But I’m too old and too spoiled: I am unworthy.

Backpack camping is absolutely a spiritual experience; perhaps the spiritual experience of our times. I just wish I didn’t stink through it.

Source: Read Full Article