Before our mothers spent Saturdays scrubbing stovetops to R&B classics they were girls — children of Detroit, Brooklyn, Newark, and other Black cities across the country. It’s the desires and identities of those adolescents author Jasmine Mans explores in her second book of poetry, Black Girl Call Home.

“Tell me who my mother was before she was my mother,” Mans says, quoting her work. “I think that’s a very important thing. Often we see these matriarchs and we never consider that.”

Mans’ words cloak those the world dismisses as “strong Black women,” in much-needed empathy. “All of those women, from my mother to my grandmother, to Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, we revere these people, but it’s important to bring them back to this most simple form: they are women,” Mans says. “They bleed, they got their periods, they cried, men left them.”

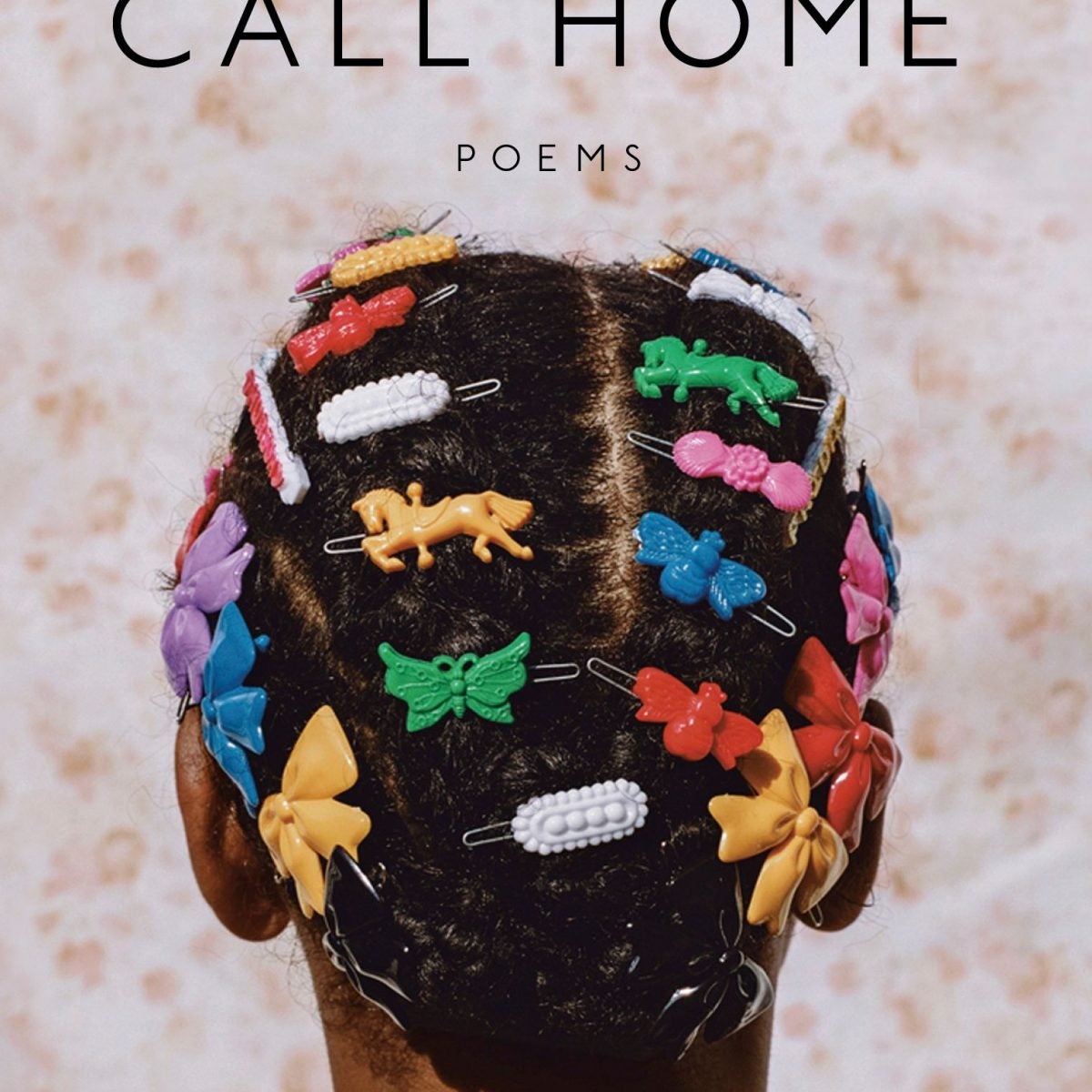

Black Girl Call Home is the highly anticipated follow-up to Mans’ debut, Chalk Outlines of Snow Angels. In the book, which has been described as a “love letter to the wandering Black girl,” by publisher Penguin Random House, Mans anchors traditional poetic stanzas with experiences she’s had and witnessed growing up.

“There are maybe four or five women inside of my body and the best Jasmine means that all of those women are sitting at the table and they’re in conversation,” she says. “They may not even be in agreement, but they are in conversation and they’re heard. I’m listening to the girl in me, but also that elder in me.”

As for the home she’s calling Black girls back to, Mans adds, “I think there are different facets of home. That’s what I was exploring in the book. You have the home that is the body, home may be the sense of faith, for some people home may be Newark.”

Parts of the book were inspired by Mans’ time at the University of Wisconsin where she was preoccupied with how the cultural landscape differed from her hometown of Newark. “I was thrust in this space with all of these white people and it wasn’t home. And it was like, how do you remember home at the University of Wisconsin?”

On each page of the book, Mans views the city from a new angle. At one point, she’s beside a tourist killing time before a flight from the nearby airport, at another she’s a spectator at a Summer block party. Throughout, she is a young Black woman who loves women trying to make sense of the art, poetry, resilience, anguish, nourishment, and neglect that make up her surroundings.

During the writing process, Mans was more focused on truth-telling than technique, she says. “It was not tapping into what it means to be a master of the craft of literature, but tapping into what my voice was and what was the voice that I heard in my house for 29 years. And what were the voices that were conjured in Newark? What were those memories? And it was my job to bring these memories and those voices to life.”

There was freedom in having a tightly defined mission, she adds. “When I got out of this battle of what it means to be great or master or the best, and I got into storytelling the book kind of blossomed.”

The book also examines how the nuances of Black girlhood intersect with rape culture, homophobia, and matrimony across generations. In one poem, a mother admonishes her newly out daughter, worried for her safety. In another, a lover asks her partner if she thinks God watches when they kiss. “There’s not a big narrative for girls who fall in love with girls,” Mans explains. “There’s not a big narrative for girls who get their heartbroken by girls.”

Though Mans says of her book, “I don’t have a new story,” she notes you will “hear the complexities of the individuals” who go through these common experiences. Her work also points out gaps in dialogue surrounding these issues.

“I think it’s how we talk about assault,” she says. “We think that for a woman to be assaulted, like a man had to drag her at a back alleyway. Right? And it wasn’t like her homeboy or the quarterback. It’s how we talk about our relationships with our fathers, and the complexities around, like, can you watch your father be a bad husband and a good dad at the same time? Those things, or just being a lesbian. How can a young girl grow up and be gay and feel safe and feel honored?”

Mans’ work sits in conversation with Bell Hooks, Donika Kelly, Candice Carty-Williams, kemi alabi, Aja Monet and others using language to rewrite archetypes of the “crazy,” and “aggressive.” It also sits beside writers of the mainstream as a true American tale.

“Black girls belong in the Canon. This is the opportunity to add another Black girl to this canon of literature and it’s tailored to Newark, it’s tailored to my personal experience that is uniquely relative to so many other Black women. It feels like Black girls are often searching for their identity and their honor and removing shame from their lives in the process of coming out. And I think it’s time for the cannon and all spaces, whether it’s television or literature to just continue to get into those details.”

At a time where debates over political corectness and anti-Blackness still plague our comunity as we beg those from outiside and witin to believe Black women — and girls — Mans’ art pleads for us to pause and try to understand one another.

“When you see a Black girl and she says, ‘I’m going to tell my story and, and I’m going to be scared, but I’m going to still show up. I’m going to say some things that I might be ashamed of and scared to say, but I’m still going to show up,’ it gives room for the Black girl behind her to do the exact same thing and so I’m showing up like the woman before me. They were girls first.”

Black Girl Call Home is available now.

Source: Read Full Article