A key UNESCO scientific report set to be released soon is understood to flag that Australia’s climate targets are still not in line with the global action needed to stop the worldwide degeneration of coral reefs, piling pressure on the Albanese government over its climate targets.

The rising threat of global warming to the Great Barrier Reef was confirmed by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) in its annual report, released on Thursday and highlights the potential for the powerful heritage authority UNESCO to officially downgrade the reef’s status to “in danger”.

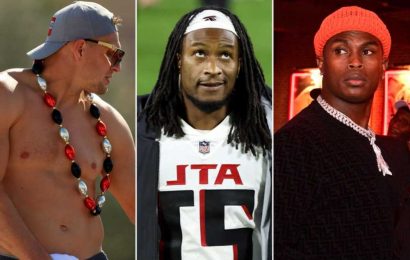

Bleaching on Stanley Reef, part of the 500-kilometre stretch of the Great Barrier Reef that copped a mass bleaching event last summer. Credit:Australian Marine Conservation Society/Climate Council/Harriet Spark

UNESCO inspected the reef in March during a mass bleaching event and is expected to release updated findings by September after last year releasing a draft report proposing its status be listed as “in danger”, which could be the first step to removing the site from World Heritage lists.

The Australian Institute of Marine Science has listed the outlook for the reef’s health as “very poor” and the agency’s chief executive Paul Hardisty said on Thursday the increased frequency of mass coral bleaching events was “uncharted territory” for the reef following the fourth mass bleaching in seven years.

“In our 36 years of monitoring the condition of the Great Barrier Reef we have not seen bleaching events so close together,” Hardisty said.

For the first time in a La Nina cycle, which usually prevents heatwaves, the southern third of the reef was this year blighted by mass coral bleaching.

The Albanese government announced on Wednesday it had gained the support needed from the Greens to legislate its target to cut emissions 43 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030. But this new target still falls short of what is needed to avoid the worst potential damage to the reef.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that even if global warming is held to 1.5 degrees, up to 90 per cent of the world’s coral reefs will be severely degraded.

The panel forecast that if the rest of the world acts consistently with Labor’s target, global warming would hit 2 degrees and lead to the degradation of 99 per cent of the world’s coral reefs.

The Australian institute’s monitoring team leader Mike Emslie said climate change was driving increasingly frequent and longer-lasting marine heatwaves.

“The peak of the most recent bleaching event in March occurred when the accumulated heat stress caused widespread bleaching but not extensive mortality,” he said.

“The increasing frequency of warming ocean temperatures and the extent of mass bleaching events highlights the critical threat climate change poses to all reefs, particularly while crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks and tropical cyclones are also occurring.”

While the institute has recorded the highest levels of coral cover in the southern reef since surveys began 36 years ago, Emslie said any gains could be reversed “in a short amount of time”.

That’s because the recent flush of coral growth was dominated by fast-growing acropora species that are particularly vulnerable to damage from bleaching caused by heatwaves and wave damage from cyclones.

“These corals are particularly vulnerable to wave damage, like that generated by strong winds and tropical cyclones,” he said.

World Wide Fund for Nature head of oceans Richard Leck said nations must “do everything possible” to halt warming at 1.5 degrees.

“Australia can do its part by rapidly driving down its greenhouse gas emissions this decade and become a renewable energy export superpower,” Leck said.

Environmental adviser Imogen Zethoven was the lead author of a Griffith University study in July that called for the reef to be listed as “in danger”. She argued downgrading its conservation status would create an opportunity for Australia to build ties by working on conservation with its Pacific neighbours who also have vulnerable World Heritage-listed reefs – including Solomon Islands, Indonesia and the Philippines.

“This is about a global policy on climate impacts and risk that could apply to any climate-vulnerable

World Heritage site,” Zethoven said.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article