CANADA is considering decriminalising heroin, cocaine and all other hard drugs after a record year for overdose deaths, a government official has announced.

The country's drug overdose death rate for the first half of 2020 – 14.6 per 100,000 people – was the highest since records began in 2016.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is facing pressure to rein in the soaring drug overdoses, although he has previously downplayed decriminalisation.

Vancouver has asked the federal government to exempt the city from part of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, which would decriminalise the possession of small amounts of drugs in the city.

Speaking last week, a spokesman for Health Minister Patty Hajdu confirmed decriminalisation was "under consideration" and said discussions with Vancouver were under way.

The number of people charged with drug possession of non-cocaine, non-heroin drugs in Canada more than tripled to 13,725 in the past decade to 2019, according to Statistics Canada.

The number of people charged with heroin possession almost quintupled, to 1,043.

Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart said the move to discuss decriminalisation "comes at a time when the overdose crisis in our city has never been worse".

Dr Mark Tyndall, an infectious diseases doctor and campaigner for decriminalisation, said the overdose epicentre is in British Columbia.

"There’s a lot of us who feel a bit burnt out about the whole thing," he told CTV News.

"So many people have died. Man, I’ve seen a lot of people die.

"There is a poison, toxic drug supply out there. They are buying poison on the street."

On average, five people die from a drug overdose every day in British Columbia, according to CTV News.

In the first nine months of 2020, nearly 1,700 people died from drug overdoses in Ontario – a 55 percent increase from the year before.

During the same period, amid the coronavirus pandemic, more people died from drug overdoses in Alberta than from Covid-19.

There is a poison, toxic drug supply out there."

Moms Stop The Harm, a national advocacy group, is also behind the decriminalisation campaign.

Co-founder Leslie McBain, whose 25-year-old son Jordan died from a drug overdose, said: "In the early 1900s, the government prohibited the sale of alcohol. What happened? Toxic, toxic alcohol.

"It killed people, gangs rolled up. The government said ‘OK, this isn’t working, let’s regulate it and sell it legally.’ People still get addicted. People still died. But it’s a safe supply."

Montreal’s city council voted to support decriminalisation this week and the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police came out in support of the move last summer.

But Trudeau dismissed decriminalisation last year, telling the Canadian Broadcasting Corp it was not a "silver bullet".

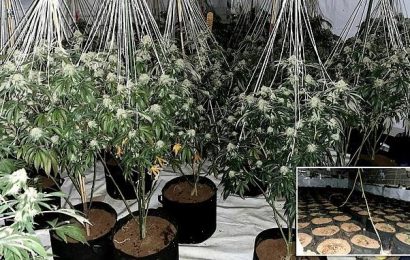

LEGAL MARIJUANA

Canada fully legalised recreational marijuana in 2018 and the country has had legal medical marijuana since 2001.

Canadians can buy cannabis and cannabis oil from licensed producers at various retail locations, but outlets are restricted to selling fresh or dried cannabis, seeds, plants and oil.

It is illegal to possess more than 30 grams of cannabis in public, grow more than four plants per household or buy from an unlicensed dealer.

Anyone caught selling the drug to a minor could be jailed for up to 14 years.

Decriminalisation and legalisation are not the same.

When drug use is decriminalised, it is no longer a criminal offence – but civil penalties could still apply, such as a treatment programme or a fine.

Meanwhile, legalisation removes all penalties for possession and personal use of a drug.

It comes as Oregon's groundbreaking law decriminalising personal drug use comes into effect today.

It became the first US state to decriminalise small amounts of heroin and other street drugs last year.

The New York-based Drug Policy Alliance – a criminal justice reform group that backed Oregon’s successful marijuana legalization effort in 2014 – was strongly behind the movement.

Those supporting the measure hope that decriminalisation will combat issues with the country's jails being filled with non-violent offenders, particularly Black people.

Portugal also decriminalised illicit drug possession and consumption in 2001.

Source: Read Full Article